Discovering The Lost Films Of John Cage

“Some people considered Cage a charlatan, and some people considered him somewhat of a prophet in terms of the way we interact with music today,” said Brown. “He essentially turned the general set-up of the musical experience upside down.”

By

Beginning in 2009, USC Thornton alumnus and adjunct instructor Richard Brown embarked on an East Coast archival tour to conduct research for his dissertation on 20th century composer John Cage. Brown was specifically interested in discovering items related to Cage’s experiments with cinema — a relatively unexplored part of the composer’s body of work.

Initially, Brown had little material to work with. The Getty Research Institute’s small collection of 20th century avant-garde papers, including a collection of material from pianist and frequent Cage collaborator David Tudor, provided some guidance — but the biggest breakthrough came when Brown was able to acquire a manuscript of a John Cage piece commissioned for American sculptor Richard Lippold.

“It was written on a paper bag,” Brown said of the manuscript. “It was just descriptions of shots of Richard Lippold working with this sculpture he had been constructing around 1953 – 1956, and it had this really beautiful score.”

But, the actual film described in the manuscript was nowhere to be found.

Determined to find the missing film, Brown began searching. His efforts eventually led him to Augusto Morselli, Lippold’s former partner and current executor of the Lippold estate.

One phone call and a short drive to Locust Valley, New York later, and Brown found himself digging around in a storage unit that was packed floor to ceiling with the late sculptor’s achieves. After several hours, Brown eventually discovered a large bin filled with old film reels.

“Sure enough, there were two tins that said ‘Cage – Lippold’ on them,” Brown recalled. “I opened them up, and you could tell right away that it was a fairly unconventionally edited film.”

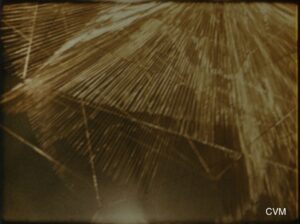

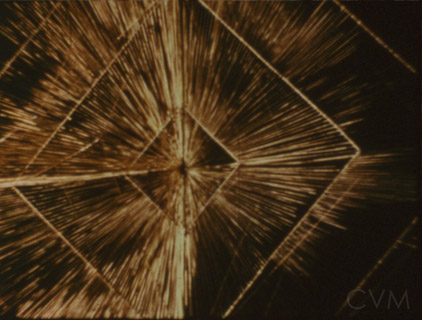

The film, titled The Sun Film, was damaged by age. But, Cindy Keefer, the director of The Center for Visual Music in Los Angeles, determined that Brown’s discovery was “definitely the original film,” and matched perfectly with the Cage score Brown had previously acquired.

Restoring the 14 minute-long film cost upwards of $9000.

The finished product is a documentary-style film chronicling Lippold’s construction of an elaborate sculpture made with 18 miles of gold wire. However, in true Cage fashion, the film is edited in a non-linear fashion using Cage’s “chance procedures” — an artistic methodology created by the composer that derives form and structure from randomly selected musical or visual elements.

“The film constantly jumps between all these different moments,” Brown explained. “It puts you in a new perspective in engagement with this sculpture, and it’s doing it in a chance-operated way.”

Cage’s cerebral approach to music and visual art is still as contentious in the arts community as it was over half a century ago.

“Some people considered Cage a charlatan, and some people considered him somewhat of a prophet in terms of the way we interact with music today,” said Brown. “He essentially turned the general set-up of the musical experience upside down.”

Though some musicians have a tough time truly understanding Cage, Brown notes the experimental composer was a passionate in his refusal to be confined by the limitations of “art” in its many forms.

Brown hopes to further The Sun Film’s legacy by uploading the work into a computer program to produce a similar form of Cage’s “chance editing.” Eventually, Brown would like to install the computer-generated film in a gallery, ensuring visitors “never be the same film twice.”

“It would project an infinite variety of edited possibilities,” Brown explained.

Brown also hopes the newfound interest in Cage’s visual works inspires young artists and musicians to explore art forms outside their preferred medium.

“I think it’s really interesting and something that music schools should really be encouraging students to interact with in new and exciting ways,” Brown noted. “Bridging that gap between a music school and an art school or a film school — an area like visual music is the perfect opportunity for that.

“It’s something as simple as just seeing these types of films,” said Brown. “There are so many ways to inspire students in new and exciting ways.”

– Jenevieve Ting and Katrina Bouza