Recording the USC Thornton Symphony

Joey Messina-Doerning, a Music Production major, took advantage of the opportunities available to him at a school as diverse at USC Thornton, and recorded the USC Thornton Symphony for his senior project.

By Jason S. Dennis

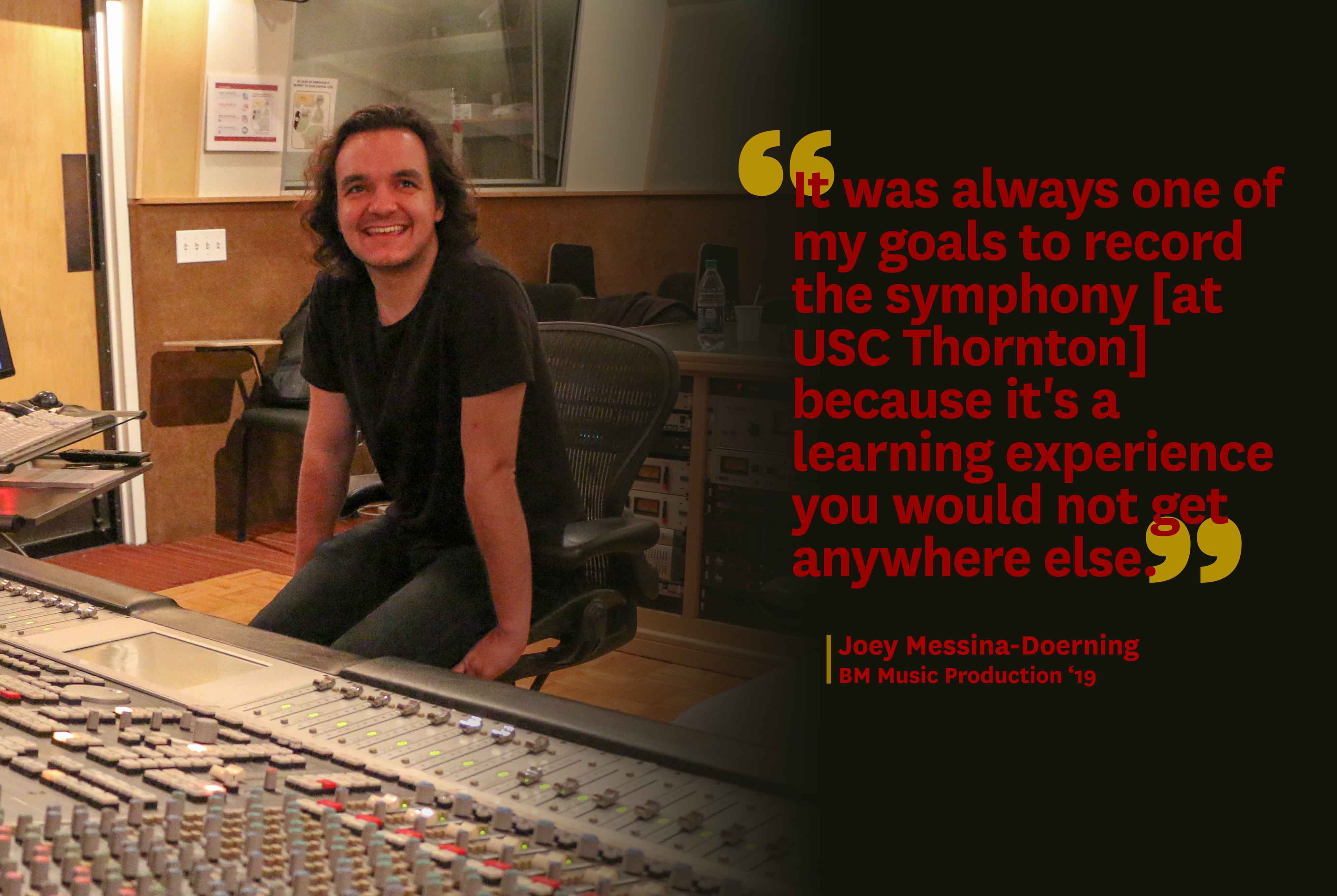

Joey Messina-Doerning (left) records the USC Thornton Symphony while Richard McIlvery advises. (Photo by Isaac Lee)

In a ground floor room of the Raubenheimer Music Faculty Building (MUS) at USC sits a massive, 80-channel SSL brand mixing console. It’s a vintage, analog piece of equipment one might find in the world’s most famous and historic recording studios.

Music Production major Joey Messina-Doerning has had his eye on it for the past four years. What intrigued him most was the fact that the console is tied into Schoenfeld Symphonic Hall, where the USC Thornton Symphony rehearses. Since he was a freshman, he wondered: Why were no students using that console to make multi-track recordings of the symphony?

“It was always one of my goals to record the symphony in there because it’s a learning experience you would not get anywhere else,” said Messina-Doerning.

Two weeks ago, as part of his senior project for the school, he became the first.

Executing the Plan

On the first Friday of March, Messina-Doerning showed up at 8:00 a.m. on campus with coffee and donuts for his crew of volunteers. He couldn’t do this the type of senior project alone. He’d convinced four other USC Thornton students to help.

Richard McIlvery, a USC Thornton professor with over three decades of service, acted as an important advocate for the project. A veteran recording engineer on major film scores and albums, McIlvery was there on his day off to lend knowledge and support.

(Left) Joey Messina-Doerning, Richard McIlvery and a volunteer assistant set up to record the symphony; (right) Messina-Doerning inspects the room before the performers arrive. (Photos by Jason S. Dennis)

“Joey’s the only one who wanted to do something on this scale,” said McIlvery. “When someone shows the interest and drive, of course I’ll help.”

As the morning progressed, Messina-Doerning and his crew hustled to execute a precise plan he’d toiled over for weeks. He’d spent hours, testing every channel on the board, every microphone, every connection. He’d attended symphony rehearsals to understand how they ran and where to place the microphones. And he’d drawn diagrams and charts, mapping out placements and cabling.

Everything needed to be perfect.

As McIlvery pointed out, “There’s very little room for error on this. You get one shot, and if you haven’t prepared correctly, you’re sunk.”

Being Prepared

Messina-Doerning was perhaps the ideal candidate for this project. His interests had shaped him for it. “I’ve wanted to work in a recording studio since I was a kid,” he said.

During his application process, he applied to conservatories as a jazz drummer because most schools didn’t have his desired major. The aspiring studio engineer thought he would have to patch together the education he wanted by either taking the few music engineering classes he could find or starting as a performance major and declaring a minor afterward.

But then he found and visited USC Thornton, meeting with Rick Schmunk, Chair of Music Technology. The timing was perfect. Messina-Doerning recalls Schmunk telling him: “I’m creating this brand-new program, and you should apply because you’re exactly the mash-up of skills we’re looking for.”

The Music Production program launched in 2015 and Messina-Doerning was among the first admitted. Since then, he has distinguished himself as a student and a professional. Last semester, he took 20 units at USC, served as a TA for a recording engineering class and worked the 1:00 a.m. to 9:00 a.m. shift as a runner at NRG Studios in North Hollywood. The studio recently promoted him to assistant engineer.

“It was tough, but it was definitely worth it, because I got to work at an amazing studio, rapidly move my way up, and learn an insane amount,” Messina-Doerning said.

The fact that he was able to augment his education with professional experience gave him not only the confidence to follow through on recording the symphony, but also the credibility he needed with faculty.

Gaining Trust

“The biggest hurdle is dealing with thousands of dollars worth of delicate gear,” Messina-Doerning said. “I had to convince people that I know how to use it, that I won’t blow up the room or drop a microphone. Also, it took scheduling across multiple departments, in two different rooms, while school is happening. I had to pull a lot of strings and make a lot of people trust me.”

The USC Thornton Symphony, led by guest conductor James Judd, rehearses while being recorded by 30 microphones. (Photo by Isaac Lee)

One of those people was Sharon Lavery, resident conductor of the USC Thornton Symphony. While open to the idea, she didn’t know Messina-Doerning. Lavery was preparing the orchestra for Rachmaninoff’s 2nd Symphony with its guest conductor, James Judd, and she needed to make sure nothing would disturb their rehearsals. That’s where a recommendation from McIlvery proved crucial.

“When you have someone like Dick McIlvery on faculty, you want to be able to collaborate,” Lavery said. “He spoke so highly of Joey, and I wanted to help make this happen. I think this type of collaboration is part of what we should be doing here at Thornton.”

Messina-Doerning now had 78 musicians and a three-hour rehearsal window to record whatever happened in the hall.

It would be a rare student experience to set up and run a professional-level, multi-track recording with a storied orchestra. At most schools, it would be impossible. And doing something like this outside school would be prohibitively expensive. McIlvery estimates between paying for musicians, studio time, and equipment, this type of recording on a motion picture score would cost between $80,000-$100,000.

Messina-Doerning was getting his money’s worth.

Messina-Doerning at the console during his recording session of the USC Thornton Symphony. (Photo by Isaac Lee)

Final Movement

By 1:00 p.m., Messina-Doerning had checked and double-checked every piece of equipment. Musicians filed in and began to warm-up. The hall sprang to life with sound.

“I’m just waiting for someone to tell me to move something,” he said during the warm-up. “There are a lot of people here. I’m trying to make it seem like a normal rehearsal, in spite of the 30 microphones.”

He ended up making some minor adjustments, but overall, his plan was sound. Just before 2:00 p.m., when rehearsal was scheduled to begin, the musicians started tuning to A, and Messina-Doerning tweaked a microphone stand over the violins and cellos. He sprinted back to MUS and hit Record. Seconds later, the orchestra launched into its first reading.

Through the speakers in MUS, the music sounded rich and dynamic. When the orchestra reached its first crescendo and the drums and timpani crashed, Messina-Doerning lit up: “Wow! That sounds so good!”

Professor McIlvery nodded and smiled.

Messina-Doerning had no control over what happened in the hall with the musicians, but he was master of every sound coming through the console. His realistic hope was to capture a clean five-minute passage. But when rehearsal wrapped at 5:00 p.m., he walked away with a complete final movement.

It took four years, but Messina-Doerning learned the answer to his question. No student had done what he’d done, because he hadn’t been there to do it. He had to blaze his own trail, one he’ll continue when he graduates in May.

“It’s the culminative effort of everything I’ve learned,” he said. “Coming into USC, I didn’t know how to use an analog console. I’d never touched a tube microphone. It’s pretty awesome that I got the opportunity to do this.”