IN CONVERSATION WITH | Bruce Alan Brown and Lisa de Alwis

By Tyler Francischine

The IN CONVERSATION WITH | series profiles the careers, accomplishments and relationships of USC Thornton faculty and alumni.

He may not don a trench coat or brandish a magnifying glass, but Bruce Alan Brown maintains a lifelong career as a detective of sorts. The chair of the USC Thornton Musicology program, who retires this year after more than three decades of service, has embarked on stacks-scouring missions across Europe in search of glimpses of the past that illuminate both the methods employed by greats like Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Christoph Willibald Gluck and the enduring legacy these composers have left on the ways music is written, performed and experienced today. Oftentimes, Brown says, it’s the surprise discoveries that become fruitful opportunities for greater inquiry.

“What I’ve produced as a scholar is largely dependent on either having seen the right things in the right order before I encounter something in the archive, or tripping across a source, so to speak: encountering something interesting which I have had the right preparation for. I make it my mission to read up on a subject and get to a point where I could illuminate its political, cultural and musical meanings,” he says. “Practically everything I’ve done is about trying to make the original sources speak to modern people in a way that allows them to be understood.”

Brown’s work allows him to become a translator, a bridge between the past and the present. He aims to instill in today’s musicologists a deep understanding of and appreciation for music’s rich heritage and cultural context.

“I explain to music students that contemporary music is really made out of our preexisting knowledge of earlier types of music, even soaked up unconsciously. When we think we’re listening to exclusively contemporary music, whether it’s popular or concert music, it’s really built from the practices and the listening habits of centuries past,” Brown explains. “There are techniques that go way, way back. Anything involving a plainchant, or a single melodic line sung in slow values against something else, rests on centuries of traditions of Catholic church music, or maybe Lutheran choral tunes. Jazz scales explore different scales besides the major or minor, which Debussy and the Russian composers in the nineteenth century used. You can’t claim, ‘I’m only interested in the new stuff,’ because whether you realize it or not, it’s all of a piece.”

Empowerment through discovery

Brown’s interest in musicology started, of course, with an interest in music. As an 8-year-old, he “obsessively played” his parents’ classical records, so they enrolled him in piano lessons. When he witnessed his piano teacher assembling a harpsichord from a kit, a lightbulb went off in his young mind. Brown’s love for early music was born.

Upon entering the University of California, Berkeley, to study music, Brown found mentorship in a harpsichord teacher, Alan Curtis, whose work combined performance with scholarly research. As an undergraduate beginning to write scholarly papers, Brown received his first taste of the thrill of discovery.

“I saw my professor making new history – not just relying on what’s published already, but actively researching and performing works that weren’t available in convenient editions,” Brown recalls. “When I was starting to write serious papers in seminars, seeing that I could come up with things that were not previously known to scholars was very empowering.”

Since graduating from UC Berkeley with a bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees in music and musicology, Brown has published an extensive collection of writings and editions, including the books Gluck and the French Theatre in Vienna, published by Oxford University Press; W. A. Mozart: Così fan tutte, published by Cambridge; as well as critical editions of Gluck’s operas Le Diable à quatre and L’Arbre enchanté.

In creating these works, Brown cast a critical eye on existing bodies of research in order to be able to produce more complete, correct histories of these beloved composers for future generations of scholars and music lovers.

“One of the more empowering moments in my whole trajectory was finding egregious errors in the complete works of Gluck,” Brown says. “That’s part of what makes musicology so fascinating: one gets to work with the actual sources. You can question a lot of received wisdom.”

Class as a conversation

As a professor and the chair of the USC Thornton Musicology program, Brown guides students through the long journey of research and dissertation writing. Lisa de Alwis (Ph.D. ’12), who received her doctoral degree in historical musicology from Thornton, says Brown’s classes were a joy because of the amount of information he provided, opening up new worlds and fresh paths of inquiry for his students.

“We are in a society where it’s all about bullet points, sound bites. What Bruce always provides is this much more interesting context around a subject, and that’s a huge difference. That’s part of the beauty of the way Bruce teaches, and he has definitely influenced me, not only as a student, but as a teacher myself,” says de Alwis, who specializes in Viennese music and culture of the late 18th and early 19th centuries and currently works as a lecturer in the University of Colorado, Boulder’s Herbst Program for Engineering, Ethics & Society.

Brown says his training at UC Berkeley taught him to treat classroom instruction as a conversation rather than a lecture. This interactive method aims to get students “hooked on the subject, developing an inherent interest in it and absorbing even more than they need.” Brown’s students have responded enthusiastically to his teaching philosophies – he’s a recipient of the USC Dean’s Award for Excellence in Teaching and the USC Mellon Award for Excellence in Mentoring.

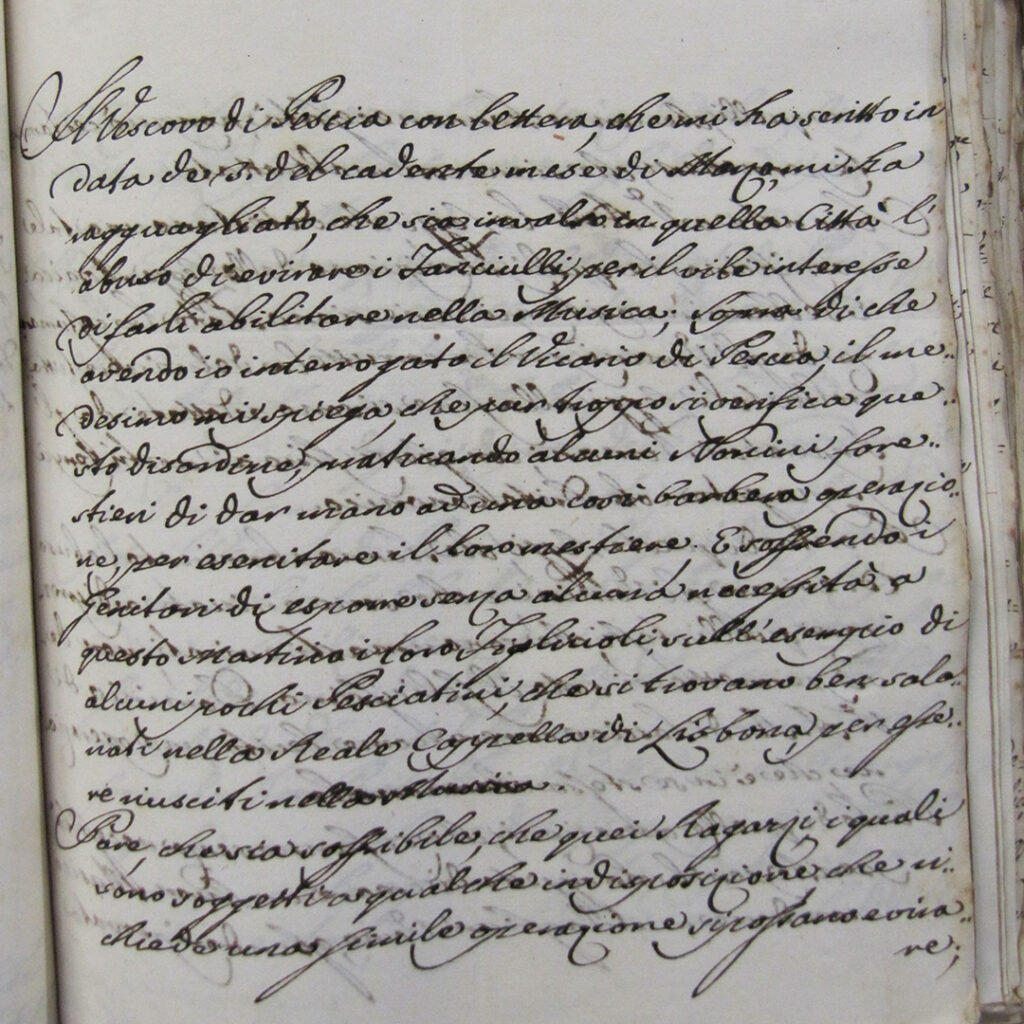

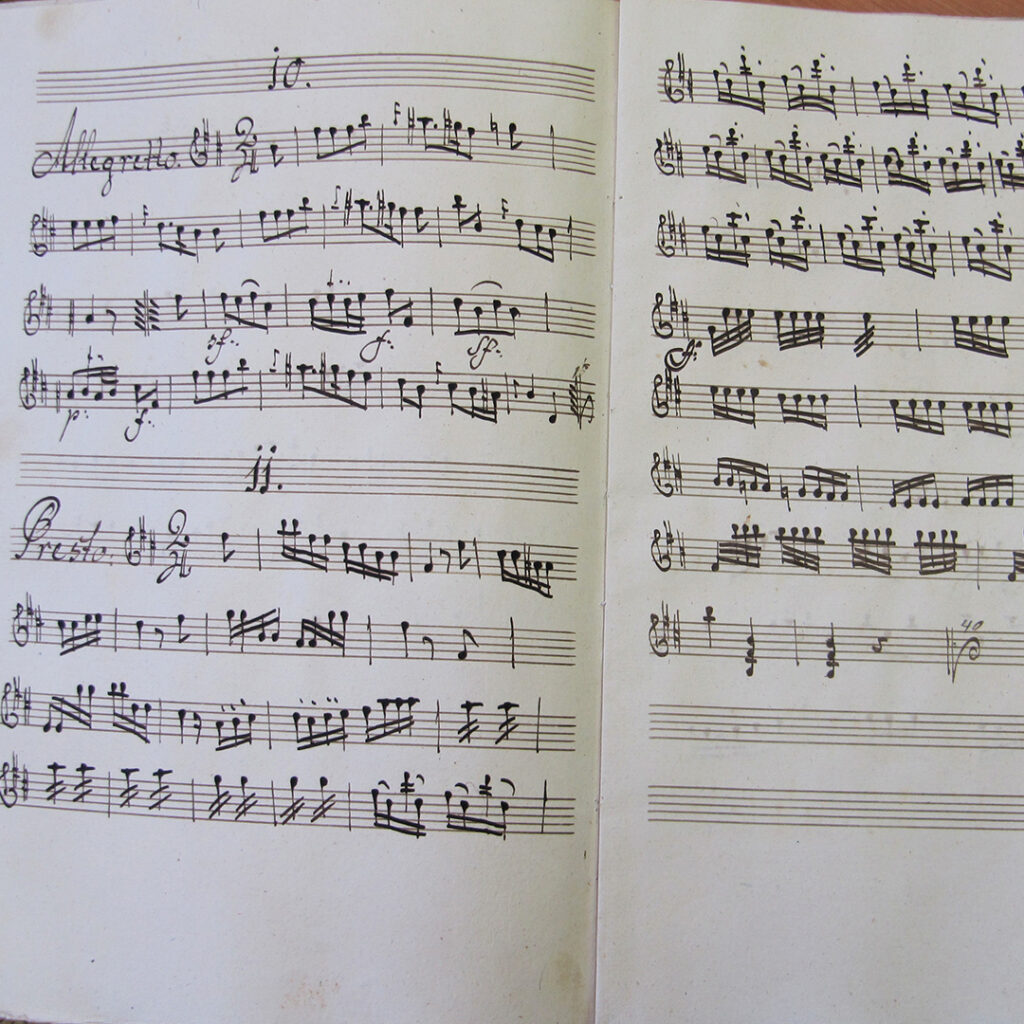

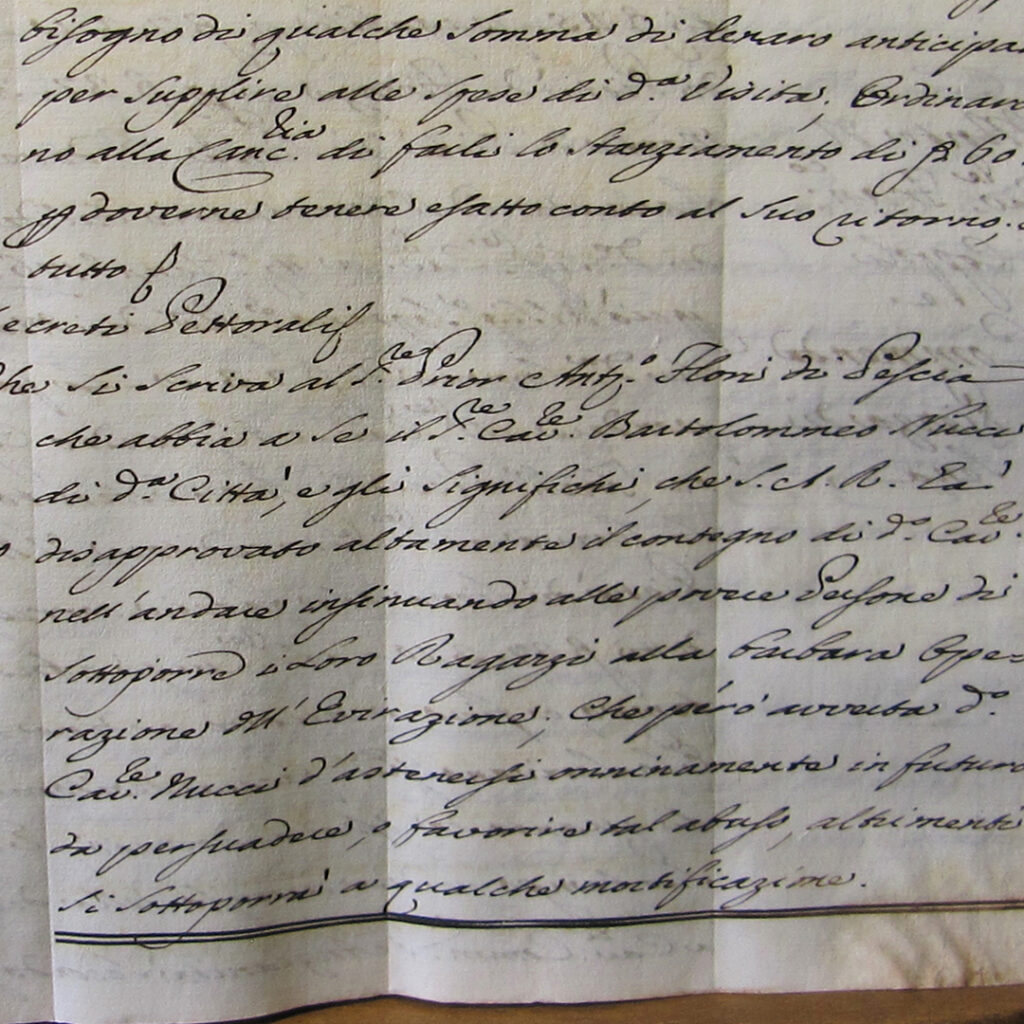

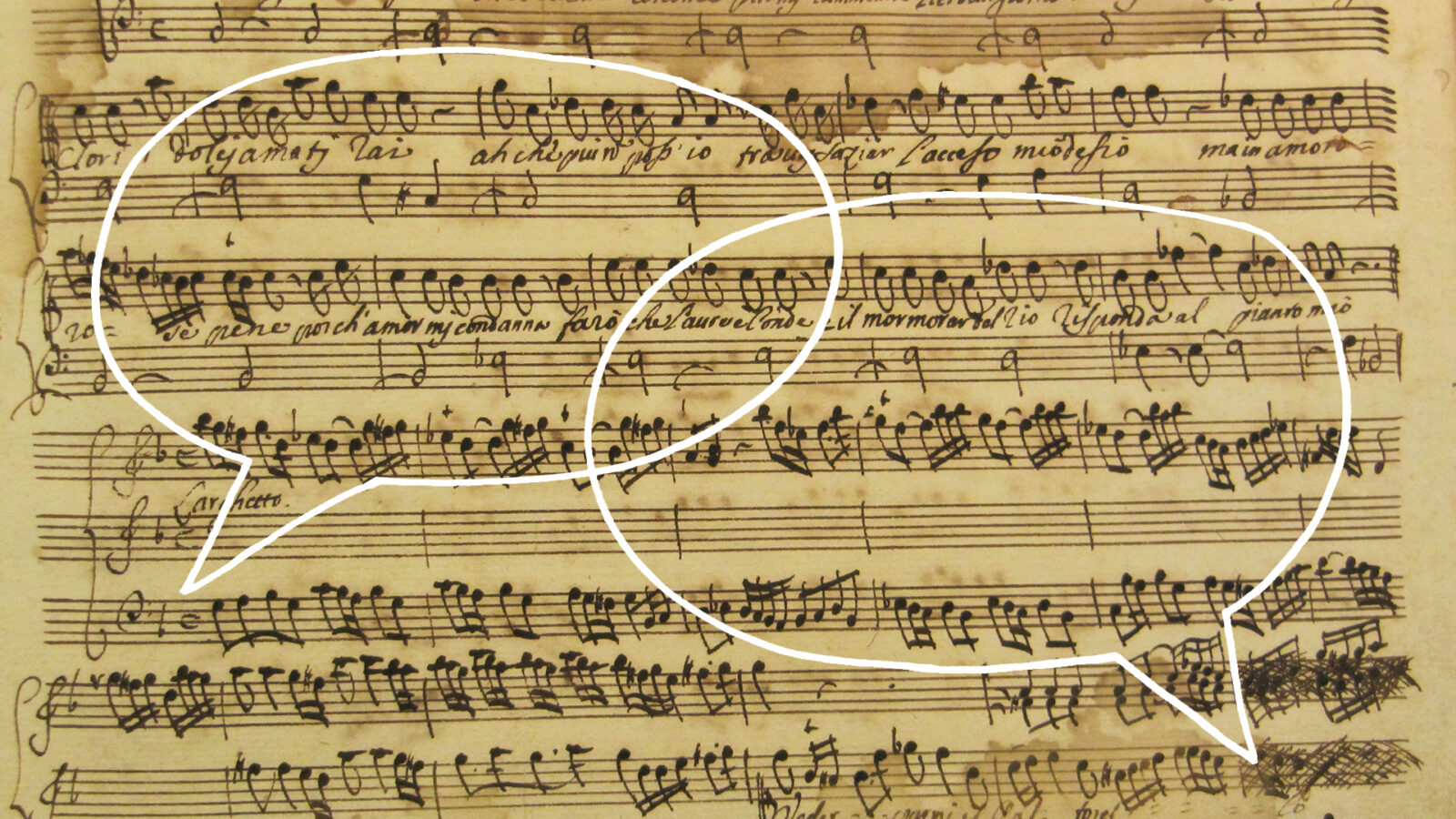

18th-century archival sources from Italy and the Czech Republic, used in some of Prof. Brown’s recent research projects. (Photos courtesy of Bruce Alan Brown.)

“I was very touched by receiving the USC Mellon Award,” Brown says. “I’m just trying to pay forward what I received as a student at UC Berkeley, where my advisors fairly quickly – that is, after we’d really proved ourselves in class – trusted us enough to open up and make us part of their circle, their network of professional contacts.”

De Alwis can attest that Brown does just that. The pair’s relationship surpassed the classroom, evolving into a friendship marked by long dinners spent speaking multiple languages like German and Italian and conversation full of shop talk about archival work, especially concerning music of the later eighteenth century, particularly opera, ballet and performance practice.

“He’s really paying it forward. All the things he described that his professors did for him, I’d say he did for me, whether that is writing recommendations, introducing me to other scholars, or bringing me to conferences,” de Alwis says. “He took me under his wing while I was still a student but continued after I graduated. It’s this seamless legacy, and I would love to pass that forward to my students.”

Careers full of wonder and beauty

De Alwis says Brown’s instruction broadens the perspectives of today’s music students, creating the next generation of expert players and deep thinkers who acknowledge and honor the music that has come before them.

“Nothing exists in a vacuum. I think that’s important for performers at Thornton to think about. It’s not just that you’re playing this isolated piece of music – it’s connected to so many things,” she says. “People like Bruce can help us understand, what was the world that this music came out of? Why is Beethoven so dramatic? It wasn’t only his personality. It was the theater and the things he was exposed to, including Gluck, that created this music, and if we understand that, we will play that music differently.”

When de Alwis finishes her thought, Brown excitedly offers, “Yes! Think about the fact that Beethoven was writing for a piano in the early stages of its development. The things he was asking it to do were right at the edge of what it was capable of, and you’re feeling that strain. That doesn’t have the same effect on a modern Steinway.”

De Alwis nods vigorously. “Perhaps, if you know some of that, you will play it differently, even on a modern Steinway.”

Reflecting on his time as part of Thornton’s faculty, Brown hopes all of his students go on to careers fueled by passion and creativity, keeping in mind that a musicology degree can open doors leading to places some have only dreamed of. For Brown, retiring from Thornton means he is closing one door, but he’s opening another to a bright future of further discovery and scholarship.

“Keep up the interest in an active way. Don’t just point to the dissertation proudly, thinking that it’s a closed book. It’s the beginning of the story rather than the end,” Brown says. “I’ll also say, my own career has not always unfolded in the directions I planned. For instance, this book on an 18th-century Neapolitan choreographer that I co-edited was a surprise result of a conference panel. I didn’t realize it was going to occupy several years of my life, but that’s what a scholarly career is about. It’s like being in a landscape garden and you turn a corner and suddenly, a different vista appears that you hadn’t known about, and you go and explore that.”

Read more

USC Thornton’s Research & Scholarly Studies Division presents a Symposium on 18th-Century Music, Theatre, and Dance

The USC Thornton Musicology Forum and USC-Huntington Early Modern Studies Institute present a symposium on 18th-century music, theatre and dance. The event will celebrate USC Thornton faculty member Bruce Alan Brown, upon his retirement. Click here to learn more.