Going Solo

By Julie Riggott

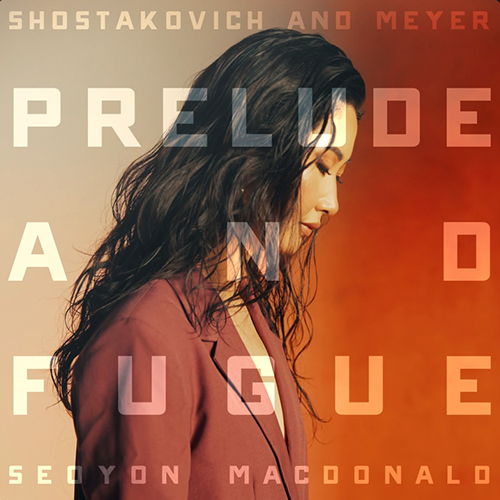

Collaborative pianist Seoyon MacDonald gets an unexpected opportunity to make the world-premiere recording of an unpublished Shostakovich work.

on all major music platforms.

On Nov. 17, Seoyon MacDonald presented the world premiere of a recording of Soviet-era Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich’s Prelude and Fugue in C# minor, an unpublished work for solo piano discovered in 2019. The opportunity fell into the hands of the USC Thornton doctoral student unexpectedly over tea with Polish composer Krzysztof Meyer at the USC Polish Music Center (PMC) a little over a year ago.

A DMA student in Keyboard Collaborative Arts, MacDonald had just heard Meyer speak (in Polish, translated by PMC Director Marek Zebrowski) in her spring semester musicology class and headed to the PMC for research for a class project. Zebrowski, Meyer and his wife were there having tea. MacDonald approached with a question she asked the director to translate: How did he exchange letters with Shostakovich years ago when he’s Polish and Shostakovich was Russian?

Meyer turned to her and said in Russian, “I speak Russian.”

MacDonald responded, “I speak Russian too.”

“He just lit up, he got so excited,” MacDonald said. “Obviously, my Russian has gotten rusty because I haven’t spoken it regularly for 12 years. I use the language infrequently when I coach Russian opera and Russian art songs to students. But I haven’t been writing essays in Russian since I quit my conservatory education.”

Born in South Korea, MacDonald attended the No. 2 Russian Music Institution (so named because the school is located in the second district) in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, studying with Olga Petrovna, and later the Basetovsky Music Institution in Almaty, Kazakhstan. She said Meyer’s invitation to share tea took her back to her time in Kazakhstan visiting neighbors and friends.

“Having tea is such a big part of hospitality and culture there. I just felt right at home,” she said. “So, we just chatted. He shared some anecdotes of Shostakovich when he visited his apartment in Moscow, and then at the end he said, ‘Okay, I have a question for you. So, you are a pianist, and if I go back home and send you a score, would you be willing to learn it and make a recording out of it?’”

It turns out Meyer had been commissioned by the Shostakovich Foundation in Moscow to complete the sketch for Prelude and Fugue in C# minor. He finished in 2020, having added a fugue to the original sketch of Shostakovich’s prelude. The piece had been performed and live streamed on Deutsche Grammophon’s YouTube channel by acclaimed Russian pianist Daniil Trifonov during COVID. But no recording exists.

“It was a very special moment,” MacDonald said, “and I felt very honored and excited to be asked to record it. It meant the world to me.”

Her Shostakovich Year

For MacDonald, it was a chance to recommit herself as a solo pianist. She had somewhat abandoned piano in high school, where she explored theater and choir. Then, as an undeclared major at the University of Northwestern, Saint Paul, she learned about collaborative piano from a professor and attended the 2012 SongFest in Los Angeles. The experience was life-changing, providing lessons on collaborative piano and introducing her to legendary composers and musicians. She also met and formed a special mentorship with Margo Garrett, a Juilliard faculty member with whom she corresponded for advice about further studies.

She went on to receive a graduate diploma in collaborative piano from the Juilliard School and a master of music degree in collaborative piano from the New England Conservatory, in addition to her bachelor of music degree in piano performance from the University of Northwestern.

As a collaborative keyboard student at Thornton, MacDonald had been focusing intensely on expanding her repertoire in chamber music, vocal and opera, orchestral, wind ensemble and other contemporary genres. Now she could step out in another direction with the Shostakovich piece.

“Over one year, I was able to kind of live with this piece,” she said, describing the piece, which is less than four minutes long, as dance-like and complex. “The prelude opens with the same theme of his C major fugue opening, but it’s in C-sharp minor! The overall aesthetics I hear a little bit of Hindemith, and there’s a little bit of Prokofiev’s sonata.”

During that time, she researched Shostakovich’s music and his life. She corresponded with Meyer (in Russian) and with the chief archivist of the Shostakovich Foundation, Olga Digonskaya Georgievna. And last spring, she worked with her advisor Alan Smith, who was the longtime chair of Keyboard Studies and director of the Keyboard Collaborative Arts program at Thornton before his recent passing, to polish it.

MacDonald learned that the piece, begun in October 1950 and completed in February 1951, was written at the same time Shostakovich composed his 24 Preludes and Fugues, Op.87, a set of pieces in each of the major and minor keys. The cycle was inspired by Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier, a set of 48 preludes and fugues. MacDonald was excited to discover recordings of the composer himself performing some of the 24 Preludes and Fugues online and used his piano playing as inspiration for her recording.

Journey of Self-Discovery

Learning about the composer’s life and artistic struggles also informed her understanding of, and connection with, the music. Shostakovich’s work had been denounced by the Soviet government — not for the first time — in 1948. He and other composers had been forced to apologize publicly for creating formalist music, that is, music with Western influences. At the time, some of his works were banned, and he was immediately removed from his job which meant losing his sources of income. But around the time he was working on the preludes and fugues, some of those restrictions had been lifted because Stalin asked him to travel as the cultural ambassador of the Soviet Union.

“He was getting awards from Stalin for big orchestral and vocal music,” she said. “But he came to the piano to explore self-expression where he felt safe. And I kind of felt his innate struggle and search for his voice without dictation or limitation to be true to himself. Shostakovich found inspiration from Bach and added something of his own flair, a Soviet modern perspective, to it. So, this piece is quite complex and abstract, quite symbolic personally.”

For MacDonald, the experience of studying this unearthed Shostakovich treasure was also a journey of self-discovery.

“The music kind of chose me,” she said. “It was at the moment that I was also struggling as an artist to figure out my identity.”

An American citizen born in South Korea and educated in Russian music schools, MacDonald was coming to realize that she didn’t need to conform to any category.

“I am a citizen of the world,” she said. “Geographically, culturally, the things that I’ve experienced have always carried me through and influenced my interests and my artistic perspective. At times, I wanted to assimilate. But here, especially living in Los Angeles and being at USC, I’m finally getting comfortable and starting to love who I am and trying to see ways to voice and feel encouraged to share my story.”

Recording the Shostakovich piece brought a sense of peace and purpose.

“This piece had been forgotten and shut down, and I’m grateful to share this music with the world,” she said. “I want this piece to mean something to people who can relate to what it’s like to be forgotten or feeling pressure to be assimilated when you don’t really fit a certain cultural category or social agenda.”

Honoring Collaborative Pianists

Even though this major recording project is completely independent of her doctoral studies, her advisor has been supportive every step of the way. The fact that Smith, and the school itself, encourage multiple interests and pursuits has been an important part of her experience at Thornton.

“Dr. Smith was nothing but an incredible support, empowering me to do whatever is in my heart,” she said. “He never said no to me. Sometimes he would say, ‘Maybe we can focus on this for now and then do that.’ Because I can get very greedy and curious and I want to do it all. He helped me prioritize and organize my life.”

Case in point, MacDonald has also taken on a book project with her musicology advisor, Scott Spencer, that will count toward her musicology minor — a first-of-its-kind book telling the stories of collaborative pianists.

“The whole reason I started this project is because during my first year at USC, I was nerding out at the Doheny Music Library, and there was no historical record of the collaborative piano field,” she said. “These are incredible musicians who have so much knowledge and skills. But they are mostly known as the pianist for Itzhak Perlman, or the pianist of Yo-Yo Ma.”

That fact made her especially sad considering USC’s history as a pioneer in the field.

“Here I am doing my doctorate at USC, which is a dream come true because USC is the first institution, not only in North America, but in the world to have started a keyboard collaborative arts department. But also, the first school to start the doctorate program in collaborative piano as well. I’m really thrilled and honored to be a part of that lineage.”

“I am fascinated by the lives of people who walked ahead of me, and I feel like their stories need to be heard,” she said. “A lot of collaborative pianists are in the shadows or behind the curtain because they are usually in a supportive role in the music industry. Since I’ve been so fortunate and privileged to work with so many wonderful teachers at different institutions and festivals, I wanted to share these enriching interactions and experiences accessible to everyone.”

The biographies could really fill multiple volumes, but for now she is starting by interviewing four female pianists — including Jean Barr, the first person to earn a doctorate in keyboard collaborative arts in 1947 at USC with Gwendolyn Koldofsky — and four males — including Alan L. Smith, the successor of Madame Koldofsky.

Smith was one of the reasons MacDonald chose to attend USC. “I wanted to study with Dr. Smith because he was an incredible pianist and pedagogue in our industry,” she said. “And I’m so grateful that USC has this incredible doctoral program with resources and stipends to help classical musicians sustain our livelihoods.”

But Smith was more than a teacher for MacDonald. He’s been her “cheerleader.”

“He believed in me more than I believed in myself. And that is a big thing because, as a music student and in the professional world, we are every hour being criticized and critiqued, pulled apart to refine and analyze our craft,” she said. “Dr. Smith was just really amazing in that regard, boosting my confidence when I didn’t have the motivation or didn’t feel secure about myself. That has been really vital for me to keep on going.”

Alan L. Smith passed away on Oct. 31, 2023, before this story was written. A longtime professor, he earned his reputation as one of the United States’ most highly regarded figures in the field of collaborative artistry.

The USC Thornton School of Music mourns the loss of Alan L. Smith, who touched the hearts of students, colleagues and collaborators alike.